This is the top article on the Wall Street Journal right now. It’s written by two former Secretaries of State, Henry Kissinger and George P. Shultz.

They are assessing the Iran deal:

While Iran treated the mere fact of its willingness to negotiate as a concession, the West has felt compelled to break every deadlock with a new proposal. In the process, the Iranian program has reached a point officially described as being within two to three months of building a nuclear weapon. Under the proposed agreement, for 10 years Iran will never be further than one year from a nuclear weapon and, after a decade, will be significantly closer.

[…]Progress has been made on shrinking the size of Iran’s enriched stockpile, confining the enrichment of uranium to one facility, and limiting aspects of the enrichment process. Still, the ultimate significance of the framework will depend on its verifiability and enforceability.

[…]Under the new approach, Iran permanently gives up none of its equipment, facilities or fissile product to achieve the proposed constraints. It only places them under temporary restriction and safeguard—amounting in many cases to a seal at the door of a depot or periodic visits by inspectors to declared sites. The physical magnitude of the effort is daunting. Is the International Atomic Energy Agency technically, and in terms of human resources, up to so complex and vast an assignment?

In a large country with multiple facilities and ample experience in nuclear concealment, violations will be inherently difficult to detect. Devising theoretical models of inspection is one thing. Enforcing compliance, week after week, despite competing international crises and domestic distractions, is another. Any report of a violation is likely to prompt debate over its significance—or even calls for new talks with Tehran to explore the issue. The experience of Iran’s work on a heavy-water reactor during the “interim agreement” period—when suspect activity was identified but played down in the interest of a positive negotiating atmosphere—is not encouraging.

Compounding the difficulty is the unlikelihood that breakout will be a clear-cut event. More likely it will occur, if it does, via the gradual accumulation of ambiguous evasions.

When inevitable disagreements arise over the scope and intrusiveness of inspections, on what criteria are we prepared to insist and up to what point? If evidence is imperfect, who bears the burden of proof? What process will be followed to resolve the matter swiftly?

The agreement’s primary enforcement mechanism, the threat of renewed sanctions, emphasizes a broad-based asymmetry, which provides Iran permanent relief from sanctions in exchange for temporary restraints on Iranian conduct. Undertaking the “snap-back” of sanctions is unlikely to be as clear or as automatic as the phrase implies. Iran is in a position to violate the agreement by executive decision. Restoring the most effective sanctions will require coordinated international action. In countries that had reluctantly joined in previous rounds, the demands of public and commercial opinion will militate against automatic or even prompt “snap-back.” If the follow-on process does not unambiguously define the term, an attempt to reimpose sanctions risks primarily isolating America, not Iran.

The gradual expiration of the framework agreement, beginning in a decade, will enable Iran to become a significant nuclear, industrial and military power after that time—in the scope and sophistication of its nuclear program and its latent capacity to weaponize at a time of its choosing. Limits on Iran’s research and development have not been publicly disclosed (or perhaps agreed). Therefore Iran will be in a position to bolster its advanced nuclear technology during the period of the agreement and rapidly deploy more advanced centrifuges—of at least five times the capacity of the current model—after the agreement expires or is broken.

That doesn’t sound like a good deal to me.

It sounds like we are trading permanent relief from sanctions. Those sanctions were built up over years of negotiations with the UN countries. Sanctions that are not easy to “snap back” if Iran breaks the deal, because they require negotiations with many different UN countries again – it won’t be automatic. That’s the “asymmetry” they are talking about in the article. Iran can break the agreement unilaterally, or just block the inspections, and the sanctions will stay off until we get agreement with the UN countries.

Here’s the former Democrat campaign worker, and now State Department spokeswoman Marie Harf:

She is confused by all the “big words” that these two Secretaries of State used in the article above.

But it gets worse!

Here’s the latest from the Times of Israel. (H/T Director Blue via ECM)

It says:

Iran will begin using its latest generation IR-8 centrifuges as soon as its nuclear deal with the world powers goes into effect, Iran’s foreign minister and nuclear chief told members of parliament on Tuesday, according to Iran’s semi-official FARS news agency.

If accurate, the report appears to make a mockery of the world powers’ much-hailed framework agreement with Iran, since such a move clearly breaches the US-published terms of the deal, and would dramatically accelerate Iran’s potential progress to the bomb.

Iran has said that its IR-8 centrifuges enrich uranium 20 times faster than the IR-1 centrifuges it currently uses.

According to the FARS report, “Iran’s foreign minister and nuclear chief both told a closed-door session of the parliament on Tuesday that the country would inject UF6 gas into the latest generation of its centrifuge machines as soon as a final nuclear deal goes into effect by Tehran and the six world powers.”

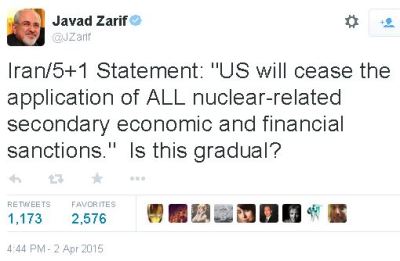

It said that Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif and Atomic Energy Organization of Iran (AEOI) head Ali Akbar Salehi made the promise when they briefed legislators on the framework agreement, and claimed the move was permitted under the terms of the deal.

Oh, I guess was wrong. This is a good deal! For Iran.

Sigh. I guess if you want to be even more horrified by the Iran deal, you can listen to an interview that Hugh Hewitt did with Wall Street Journal columnist Bret Stephens, and there’s a transcript as well for those who would rather read about the incompetence of the Obama administration rather than hear about the incompetence of the Obama administration.