What is the Rare Earth hypothesis?

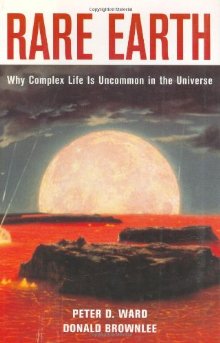

It’s the thesis of a recent book written by two scientists at the University of Washington.

Here’s the blurb:

What determines whether complex life will arise on a planet? How frequent is life in the Universe?

In this exciting new book, distinguished paleontologist Peter D. Ward and noted astronomer Donald Brownlee team up to give us a fascinating synthesis of what’s now known about the rise of life on Earth and how it sheds light on possibilities for organic life forms elsewhere in the Universe.

Life, Ward and Brownlee assert, is paradoxically both very common and almost nowhere. The conditions that foster the beginnings of life in our galaxy are plentiful. But contrary to the usual assumption that if alien life exists, it’s bound to be intelligent, the authors contend that the kind of complex life we find on Earth is unlikely to exist anywhere else; indeed it is probably unique to our planet.

With broad expertise and wonderful descriptive imagery, the authors give us a compelling argument, a splendid introduction to the emerging field of astrobiology, and a lively discussion of the remarkable findings that are being generated by new research. We learn not only about the extraordinary creatures living in conditions once though inimical to life and the latest evidence of early life on Earth, but also about the discoveries of extrasolar planets, the parts Jupiter and the Moon have played in our survival, and even the crucial role of continental drift in our existence.

Insightful, well-written, and at the cutting edge of modern scientific investigation, Rare Earth should interest anyone who wants to know about life elsewhere and gain a fresh perspective on life at home which, if the authors are right, is even more precious than we may ever have imagined.

And here’s a review by Library Journal:

“Renowned paleontologist Ward (Univ. of Washington), who has authored numerous books and articles, and Brownlee, a noted astronomer who has also researched extraterrestrial materials, combine their interests, research, and collaborative thoughts to present a startling new hypothesis: bacterial life forms may be in many galaxies, but complex life forms, like those that have evolved on Earth, are rare in the universe. Ward and Brownlee attribute Earth’s evolutionary achievements to the following critical factors: our optimal distance from the sun, the positive effects of the moon’s gravity on our climate, plate tectonics and continental drift, the right types of metals and elements, ample liquid water, maintainance of the correct amount of internal heat to keep surface temperatures within a habitable range, and a gaseous planet the size of Jupiter to shield Earth from catastrophic meteoric bombardment. Arguing that complex life is a rare event in the universe, this compelling book magnifies the significance — and tragedy — of species extinction. Highly recommended for all public and academic libraries.”

Note that Peter Ward is a militant atheist (he has debated against Stephen C. Meyer), and Donald Brownlee is an agnostic. These are not Christians, nor are they even theists. However, I have the book, I have read the book, and I recommend the book. I usually have this book on my shelf at work for show-and-tell.

Now for the latest news about the hypothesis of the book. (H/T Brian Auten of Apologetics 315)

There are always going to be optimistic predictions by scientists who need to attract research funding, but those are hopes and speculations. The data we have today says Earth is rare. The number of conditions required for complex life of any kind is too high for us to be optimistic about alien life in this galaxy, at least. And as the number of requirements for life roll in, the odds of finding alien life that can contact us get slimmer and slimmer.

From the UK Daily Mail. (H/T Peter S. Williams)

Excerpt:

Dr Howard Smith, a senior astrophysicist at Harvard University, believes there is very little hope of discovering aliens and, even if we did, it would be almost impossible to make contact.

So far astronomers have discovered a total of 500 planets in distant solar systems – known as extrasolar systems – although they believe billions of others exist.

But Dr Smith points out that many of these planets are either too close to their sun or too far away, meaning their surface temperatures are so extreme they could not support life.

Others have unusual orbits which cause vast temperature variations making it impossible for water to exist as a liquid – an essential element for life.

Dr Smith said: ‘We have found that most other planets and solar systems are wildly different from our own.

‘They are very hostile to life as we know it.’

‘The new information we are getting suggests we could effectively be alone in the universe.

‘There are very few solar systems or planets like ours. It means it is highly unlikely there are any planets with intelligent life close enough for us to make contact.’ But his controversial suggestions contradict other leading scientists – who have claimed aliens almost certainly exist.

These arguments are actually quite useful, and I include them in my standard list of scientific arguments for theism. (See below) You have to know this stuff cold. Most people believe in aliens because they watched movies made by artists. As a result, they think that humans are nothing special and that God is not interested in us in particular. Which is very convenient for them, because it means they can do whatever they want and not care what God thinks about what they are doing. If you want to defend against the idea that humans are nothing special, and that we were not placed here for a purpose, and that we are not accountable and obligated to seek and know the Creator/Designer, then you’ll need more than feelings. You’ll need science. You’ll need the best science available.

Related posts

- The origin of the universe from nothing

- The fine-tuning of the cosmological constants to permit life

- The fine-tuning of the galaxy, solar system, and planet to permit life

- Origin of the building blocks in the simplest replicating cell

- Origin of biological information in the simplest replicating cell

- Sudden origins of all major body plans in the Cambrian explosion

- Irreducible complexity in molecular machines

- The limits on what natural selection and random mutation can do

- Peer-reviewed paper says there is no atheistic explanation for the Cambrian explosion

- Does the Cambrian explosion disprove Darwinian evolution?