I write military history posts every once in a while, to remind people to honor those who fought for our freedoms. If you check out my “What I am Reading” page on this blog, then you’ll see that I’ve been reading a fair number of books about the Korean War west of Chosin, and Guadalcanal. These were both Marine actions, so for Memorial Day, let’s talk about one Marine from each action.

Chronologically, the battle of Guadalcanal comes first. This engagement involves naval conflicts as well as land conflicts. I’ve read several books about it; “Neptune’s Inferno: The U.S. Navy at Guadalcanal” (naval), “The Cactus Air Force: Air War over Guadalcanal” (air), and “Midnight in the Pacific: Guadalcanal — The World War II Battle That Turned the Tide of War” (land). I also play a simulation game called “War on the Sea” where I get to control the American navy and air force. And I have already pre-ordered a new wargame about it: “Guadalcanal: The Battle for Henderson Field“.

The operation starts in August 1942, two months after the Americans scored a shocking victory against a superior Japanese force at the Battle of Midway, sinking 4 Japanese carriers in exchange for the loss of one, the USS Yorktown.

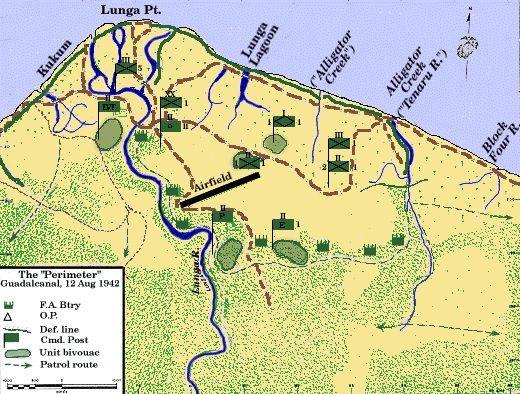

(Image source credit for above Solomon Islands map)

In early August 1942, Operation Watchtower targeted the Japanese-held Solomon Islands, primarily Guadalcanal, where Japan had established a foothold and was building an airfield to threaten Allied supply lines to Australia. The Japanese, having expanded rapidly across the Pacific since Pearl Harbor, held the strategic initiative, with strong garrisons and naval dominance in the region. Their air forces, including the Mitsubishi Zero, outmatched early American aircraft like the Wildcat in maneuverability and range. Japan’s navy, with formidable carriers and battleships, held a slight edge over the U.S. Pacific Fleet, depleted after Pearl Harbor but bolstered by carriers like the Enterprise and Hornet.

One figure who really stood out to me during the land campaign was an enlisted Marine named John Basilone.

I saw a new New York Post article about Basilone authored by Rich Lowry, so let’s see what he has to say:

Born in Buffalo and raised in New Jersey by his Italian-American parents, he enlisted in the Army in the 1930s as a teenager. Then, after a stint as a civilian, he signed up for the Marines in 1940.

During the Battle of Guadalcanal in 1942, he almost single-handedly held off a massive assault by a Japanese regiment against two machine gun sections he commanded.

[…]When the Japanese disabled one of the American gun crews, Basilone moved another machine gun into position and personally manned it, and also repaired another gun under heavy fire.

When they needed more supplies, Basilone ran through Japanese lines to get the ammunition, defending himself with his Colt .45.

He fought for days and, by the end, he and his comrades had basically annihilated the Japanese attackers.

Basilone lost his asbestos gloves in the chaos and still handled the searing machine gun barrels, sustaining burns on his hands.

[…]Nash Phillips, a private who was wounded in the fight, recalled, “Basilone had a machine gun on the go for three days and nights without sleep, rest or food.”

He was awarded the Medal of Honor for that action (citation), but he wasn’t done serving his country:

Basilone was awarded the Medal of Honor and afforded, appropriately, a hero’s welcome back in the States. He participated in the campaign to sell war bonds.

His conduct at Guadalcanal would be more than enough valor in one life for the rest of us, but Basilone wanted back in the fight.

The Marines told him he was more valuable at home and denied his request. Basilone insisted, and the Marines eventually relented.

He was a machine gun section leader again in February 1945, on the first day of the invasion of Iwo Jima, a godforsaken hunk of volcanic rock in the middle of the Pacific. The dug-in Japanese chewed up the Americans on the beaches.

Basilone flanked a Japanese blockhouse, climbed atop it, and took it out on his own. He then led a Marine tank out of a minefield, before getting fatally hit.

For this action, he posthumously received the Navy Cross. The citation refers to him as “stouthearted and indomitable,” and praises “his intrepid initiative, outstanding skill, and valiant spirit of self-sacrifice.”

The war against Japan was one of our most noble wars. Prior to our entry in the war, Japan was already invading neighboring countries, and committing atrocities against unarmed civilians. We had every right to fight back once they attacked us, and to use every means necessary to stop their brutal aggression.

Since there is still space in this blog post, let’s fast forward a few years to the Korean War, and look at a famous battle in it, the Battle of the Chosin Reservoir. For this theater, I recommend several books from my reading list. The best one is “On Desperate Ground: The Marines at The Reservoir, the Korean War’s Greatest Battle“. And I also liked “Colder Than Hell: A Marine Rifle Company at Chosin Reservoir” and “The Last Stand of Fox Company: A True Story of U.S. Marines in Combat“. There are actually two battles going on at the reservoir, one with the U.S. Marines on the west side of the reservoir, and one with the U.S. Army on the east side of the reservoir.

So, recall that the Korean War started with an invasion by North Korean communists against peaceful South Korea. America stepped in to defend South Korea from this aggression.

In late November 1950, the Battle of the Chosin Reservoir unfolded in North Korea’s frozen mountains, where the U.S. 1st Marine Division, under Major General Oliver P. Smith, faced a dire situation. Following the successful Inchon landing, General Douglas MacArthur and Major General Edward “Ned” Almond, pursued an aggressive push to the Chinese border at the Yalu River. MacArthur ignored October 1950 intelligence of 120,000+ Chinese troops crossing the Yalu, while Almond’s orders to advance disregarded the frozen, mountainous terrain.

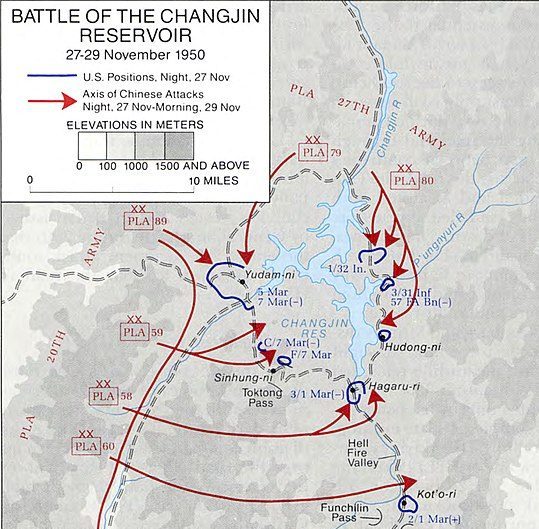

Make sure you find Toktong Pass in the image! It’s important!

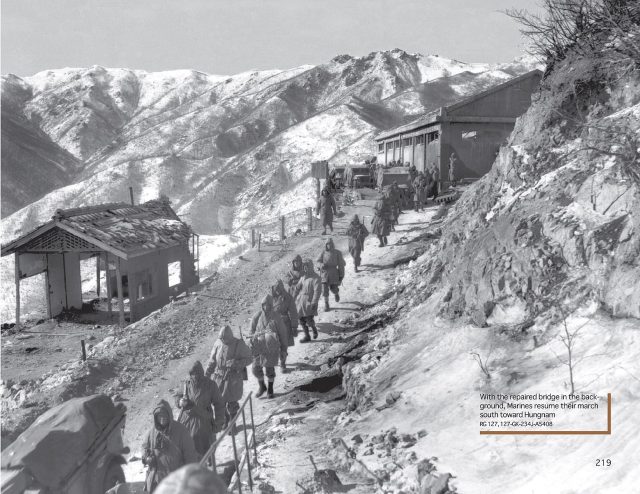

By late November, 30,000 UN troops, including 20,000 Marines, were strung along a narrow 78-mile-long mountainous road from Hungnam to Yudam-ni, with key positions at Hagaru-ri and Toktong Pass. The Chinese held the initiative, outnumbering UN forces 10-to-1 in places. Bitter cold weather (-30°F) limited the U.S. air advantage, with Marine Corsairs from Hagaru-ri’s airfield providing vital support. Smith’s cautious advance, defying Almond’s dismissal of the Chinese (“Don’t let a bunch of Chinese laundrymen stop you!”), ensured supply stockpiles and an airfield at Hagaru-ri, critical for evacuations and reinforcements. His foresight preserved unit cohesion and saved 15,000 Marines from annihilation.

If you noticed that phrase “preserved unit cohesion”, I’ll just give you a hint that the U.S. Army forces east of Chosin were more beholden to the recklessness of MacArthur and Almond, and made no provisions for the Chinese ambush. Unit cohesion was lost and our forces were annihilated. You can read all about that in “East of Chosin: Entrapment and Breakout in Korea, 1950“. It’s a tough book, but shows the value of planning and caution when dealing with unknown enemies in mountainous terrain during the winter.

I previously blogged about William Barber and his Fox Company‘s heroic stand at Toktong Pass. Captain Barber’s Fox Company held Toktong Pass for five days against 1,400 Chinese, allowing 8,000 trapped Marines in the north to move south down the road to escape defeat. Fox Company received only minimal support from light helicopters, because of the cold, snowy weather and roadblocks to the north and south.

So today let’s take a look at one of the Fox Company Marines who held the Toktong Pass for 5 days, with this article from Task and Purpose:

On Thanksgiving 74 years ago, at the height of the Korean War, the sound of gunfire abruptly woke Marine Pvt. Hector Albert Cafferata Jr. He and his squad held Fox Hill during the Battle of Chosin Reservoir, and a regimental-sized Chinese People’s Volunteer Army — a force of approximately 1,400 soldiers — sprung an ambush two hours past midnight.

Cafferata, then 23, was assigned to Company F, 2nd Battalion, 7th Marines, 1st Marine Division. He and over 200 Marines were tasked with protecting the Toktong Pass, an escape route through the Nangnim Mountains near the Chosin Reservoir in modern-day North Korea.

An initial hail of gunfire, grenades, and mortars knocked out nearly everyone in Cafferata’s squad, creating a weak spot in the defense perimeter, but Cafferata continued fighting, without a jacket in the pre-dawn winter cold. The Washington Post reported that fellow wounded Marine Kenneth Benson was initially blinded by a grenade blast during the attack but continued helping Cafferata by reloading his rifle.

Cafferata also landed on a desperate but ingenious way to send enemy grenades back toward the enemy.

“For the rest of the night, I was batting hand grenades away with my entrenching tool while firing my rifle,” Cafferata said in a 2001 interview with Florida’s Charlotte Sun newspaper. “I must have whacked a dozen grenades that night with my tool. And you know what? I was the world’s worst baseball player.”

Described as “Stouthearted and indomitable” in his Medal of Honor award citation, Cafferata managed to repel the ambush single-handedly, though it was temporary. The Chinese soldiers launched a vicious second wave in the morning hours.

During the fierce fighting, a grenade landed near a group of wounded Marines, and Cafferata threw it back under heavy fire. This time, it detonated after leaving his hand and severely wounded his right arm and hand with shrapnel. That didn’t stop him, though.

“Courageously ignoring the intense pain, he staunchly fought on until he was struck by a sniper’s bullet and forced to submit to evacuation for medical treatment,” reads the award citation.

Before getting evacuated, Cafferata is credited with killing 15 enemy soldiers and wounding several others. In Peter Collier’s 2003 book “Medal of Honor: Portraits of Valor Beyond the Call of Duty,” Cafferata’s Marine officers recalled how they counted about 100 dead Chinese soldiers where he had held the line. Still, they did not report that number because “they thought that no one would believe it.”

His Medal of Honor citation is here.

So, it’s Memorial Day, and it’s a time for Americans to take time out to think about the respect and gratitude that we owe to people who risked their lives for their friends.

We owe our liberties in large part to the American heroes who fought against imperialism and communism. It’s sad that we have so many people going through our schools and our universities, and coming out with ignorance of these heroes, and a lack of patriotism.

As a non-white legal immigrant to the United States, I’ve made it a major part of my life to go back in time and learn about the sacrifices of the people in our armed forces. You should make the effort, too. I don’t watch television, I am not subscribed to any streaming services, and with RARE exceptions, I don’t watch modern movies. My head is always in the past, learning about people who lived tougher lives than mine, and performed greater deeds fighting against evil than I ever will.

Reading this post and sharing it on social media would be a good start! Many Americans leave school unaware of the sacrifices of our heroes in the armed forces. Let’s share their stories to inspire gratitude in the next generation.